In the dawn, armed with a burning patience, we shall enter the splendid Cities

Rimbaud

Darren Tofts ::: Swinburne University of Technology

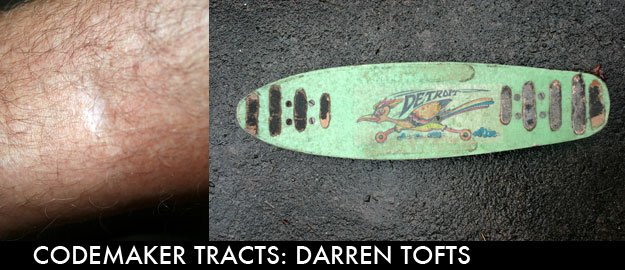

I think it was around January ‘76. Lairising at speed I was upended by the resilient and time-worn inevitability of a road-side curb. A stray stone, one of the myriad instances of invisible urban kipple, chaperoned my fall back to terra firma, puncturing flesh in a tidy, almost surgical perforation. Both decks still exist, one in my garage and the other in reassuring situ on the corner of Russell and Bourke; respective testaments to the archive drive and the enduring social ecology of urban space. Despite the intervening years, that familiar coordinate has become a kind of intransitive verb, for in Melbourne you are always traversing Russell and Bourke. But this particular inscription was especially acute, since it is indelibly written on the body with the intimate longevity of a freckle.

If you look closely you can still see it. Just above the left ankle. A puncture mark that became infected, accelerated into septicemia and eventually degenerated into an ulcer that an intense course of penicillin could not assuage. For years it was numb, uncannily tactile yet resistant to the touch and the petulant agitation of sharpened fingernails. With the intervening years the nerves have repaired themselves, re-generated, like so many urban renewal projects.

Skateboarding was one of the first forms of play that re-defined the bland utilitarianism of urban infrastructure, radically altering its flows, its rhythms and its command and control of the street. In fact skateboarding was an incipient form of cyberpunk, finding its own use for things through accident, happenstance and casual opportunism. Stacey Peralta’s Dogtown and Z-Boys (2001) documented how the spillways and concrete wastelands of California were claimed by second generation skateboarders as a new kind of territory, aggressively re-purposed through the ballsy speed of a mobility that was different from walking, cycling or running and, for that matter, skateboarding as it had been understood up to that time. During the long drought of 1976 sidewalk flâneurs like Tony Alva and Jay Adams tactically invented new moves for and attitudes towards skateboarding by détourning people’s empty swimming pools in a form of fractious guerrilla aesthetics, an imaginative and gymnastic transit through confined and defined space, years before the notion of the skate bowl or vert had even been conceived.

In his splendid book on the pleasures of pedestrian Paris, The Flâneur, Edmund White insists that the City of Light “is a world meant to be seen by the walker alone, for only the pace of strolling can take in all the rich (if muted) detail”. Thinking back on my own experience as a sixteen year old, I would anachronistically concur with Monsieur White, with the qualification that a set of Cadillac polyurethane fats, Detroit trucks and a fibreglass flexi-deck make for an even smoother ride. Or, to appropriate and remix Charles Baudelaire on the figure of the city loiterer, the “observer is a prince who, riding a skateboard, takes pleasure everywhere”.

This small and apparently innocuous mark which I’ve carried around as part of me since the late 70s speaks of our almost forgotten corporeal relationship to the urban spaces we inhabit everyday and, in particular, the pleasures we derive from this relationship. I’m not simply talking about the everyday experience of “walking in the city”, as Michel de Certeau would have it. I’m talking about the residue of the street that builds up on the soles of your feet, the dust and fumes that irritate the mucous membrane, the seduction of the olfactory imagination with the aromas of grimy restaurant exhaust fans, caressing the air with the spunk of a dozen promiscuous cuisines. Far from being perambulatory, the experience of the street is a kind of tango, a hustle involving the physical negotiation of bodies in unavoidable, unwanted contact and the obscure, balletic attempts to avoid it or court it; the radiant heat and sweat oozing from buildings as they metabolize the atmospheric ebbs and flows of ancient diurnal rhythms.

This corporeal sensation of the built environment as a kind of rutting is almost forgotten because our first hand experience of the funk and rugged grit of the street has been intimately modified by the smooth wireless locutions of being elsewhere. The here and now has been seamlessly and effortlessly relegated to the status of regrettable background noise, an omnipresent there invoked by the intimate apparel of personalized mobile media. The hand-held screen has become a portal, the escape clause of a “grammar for being elsewhere” as the critic H. Porter Abbott might say, that persistently changes our relationship the stuff of the street.

The more sedentary pleasure of walking and talking in the city, gesticulating to absent, unseen others has replaced the vertiginous thrill of gunning it down the projectile grid of Melbourne’s unanimous streets and laneways. But the memories of that vibe are indelibly part of the streetscape that I move through every time I pound the pavement through my beloved vectoral Melbourne. Walking, like skateboarding, has its codes, its syntax of sensation and muscle memory, the diverse semantics of its lyrical strolling and delirious mediated speed. But a memory, mediated or otherwise, is quite different from and far more evocative than the telepresence of cellular telephony. Listen, I don’t care how piquant or memorable that SMS was that disengages you from the world. It ain’t no Madeleine dunked in tea and the uncontrolled wonders of memory it is capable of unleashing. I’m still acutely aware of the sonic residues that saturate my experience of the city, attuned to the tinny proximity of the trannie, the café muzak along Swanston Street and the formidable memory theatre that is the LP archive assembled from these very streets. Involuntarily I hear the varied, iconic echoes of Tony Christie’s “Through the avenues and alleyways” from myriad auditions as I haunt the sites of long-gone record stores like Archie ‘n Jugheads, Pipe, Gaslight and Batman, or vestigial second-hand bookshops that now serve bubble-tea, cheap porn, globalized coffee and Korean kitsch.

Skateboarding is a form of codemaking avant la lettre. It is a form of writing that weaves the city, integrates its threads as a kind of tapestry, the warp and weft of a continuous negotiation of discrete, GPS-precise locations into the flow, grace and rhythm of a kinetic mise en scène that is as uniquely individual to me as it is to countless conjugated yous. For years I have been photographing faded anachronistic advertising, logos and street paraphernalia in the Melbourne CBD as well as the northern suburbs in which I grew up and currently live. I realise now that this visual semiotic landscape is the sedimentary record of Melbourne’s corporate muscle memory, its remembrance of things past their use by date. But this overlap of the past with many successive presents is, like a heritage overlay, also a remembrance of things fast, a persistent algorithm that continues, and will continue, to entwine our immediate experience and memory of the urban landscape we call home.

Postscript, 12.29 am, 10/1/11.

I recently bought a pair of red suede Converse runners. A curious name, runners, since I very rarely run in them, though remember a younger self that did. What is most uncanny about them is the immediate association of a kind of movement more akin to dancing than running or even walking. But not dancing in the street, dancing the street, a sensation of gliding, bending and curving, a series of sculptural vogues riffing off the embodied city that transcend the mechanical, algorithmic binary of left/right. This is a different kind of code, a bio-spatial rumba that attunes you to a speed unlike anything cranked out by even the fastest dual core processors. When you are courted by its vibe, it’s time to hit the deck. I feel a Lygon Street limbo coming on.

Dedicated to Melbourne Sports Depot, Northland Shopping Centre, East Preston, c. 1975.

Pingback: Darren Tofts » Hitting the Deck: traversing the embodied city